Our book club had a fantastic weekend of culture, food and drink in Liverpool in March. Just before our train home we ended up spending a couple of hours in the gorgeously refurbished Central Library, where there were two books on display that really caught the eye. One was Speculum Aureum Decem Praeceptorum, a collection of sermons based on the Ten Commandments by the fifteenth-century monk Henricus Herpf. It was published in 1481 by the Nuremberg printer and goldsmith Anton Koberger at a time when the Continental printing industry was beginning to flourish – Caxton only printed his first book in 1473, when the presses in Cologne, Bruges and Nuremberg were already going strong. It appears that Herpf ‘s meditations had a healthy readership regardless of political or confessional divides, given John Dee’s library contained a heavily-annotated book of his sermons. (Abe Books is currently selling one of them for £18,435.65, plus £29.83 p&p. I think I’ll pass.)

If I’m honest, the real interest is the material detail that hints at how it was consumed. It’s bound in pigskin with its chain still attached – the last link has a bolt that is shaped to fit into a slot where it could run freely, presumably with other books in a collection. It’s a book made to be housed with others, which hints at an intellectual or devotional community – in this case, an institution in Gerpinnes in the Belgian region of Hainaut.

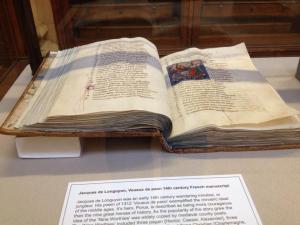

The second book of note is a stunning illuminated manuscript called Voeux du Paon (the vows of the peacock), written a century earlier in 1312 and dedicated to Thibaut de Bar, bishop of Liège. This copy (Phillipps MS 2582) is bound in 18th-century mottled calf and the head librarian tells me that it was bought in 1957 from a collection that was originally acquired by the antiquarian Sir Thomas Phillipps in the early 19th century. Phillipps was clearly an enthusiast of fourteenth-century verse romance, since he owned two other versions of the Voeux, all of which are from the same manuscript tradition with little dramatic variation among them. When the medieval scholar Edward Billings Ham compared the three in 1929, he found that what is now the Liverpool manuscript has less regional French dialect than its companions but the scribe’s calligraphy is not as fine as the others.

Verse romance, which on the whole (generalisation alert) was consumed orally, tends not to have quite so much in the way of iconography and this conforms to that – just 20 illustrations among the 132 leaves of vellum.

The Voeux du Paon, which is part of a cycle of texts around Alexander the Great, switches between warfare and leisure, between the battlefield and the courtly milieu; it starts off with the siege of the castle of Epheson where the attacker, Clarus, is trying to make Fesonas, the sister of Gadifer, marry him. Gadifer has some powerful allies, though; namely, the venerable knight Cassamus and Alexander himself. During the enforced leisure of the siege, the lords and ladies gather and the knight Porrus kills Fesonas’s peacock. To calm the gathering, Cassamus suggests the peacock be the focus of vows among the company, whereupon the knights pledge to perform great deeds.

My medievalist friend Mike Leahy tells me that there’s a very probable link between these peacock vows and Edward I’s feast at Westminster in 1306 where he pledged over a feast of swans to avenge various acts of aggression by Robert the Bruce and to fight the Saracens in the Holy Land. The feast of swans saw over 200 lords knighted at the same time, so it’s a key moment in the development of the ideology and culture of chivalry, particularly given Edward I’s propensity to appropriate Arthurian legend. It looks like the Longuyon text is therefore a classic example of refictionalising an original act, and how that piece of fiction in turn helps to create cultural rituals – a bit like the way that the jousts in Sidney’s Arcadia and the Elizabethan Accession Day tilts inform and create each other’s mythology. There was a subsequent rash of verse imitations of the peacock vows, too, such as the vows of the sparrowhawk and the vows of the heron (the latter dramatising Edward III’s decision to embark on what would become the Hundred Years’ War).

The transmission history of the Voeux du Paon is significant not just for initiating the cycle of texts around vows. It also marks the first appearance of the Nine Worthies, the three triads of great heroes whose examples span pagan, Old Testament and more recent history. They are: Hector, Alexander and Julius Caesar; Joshua, Judas Maccabaeus, and David; and Arthur, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Bouillon, who successfully besieged Jerusalem in the First Crusade. All are deemed by Longuyon as the perfect noble warriors, neatly co-opting the emerging cult of chivalry into a divinely ordained historical continuum. The Nine Worthies became embedded into high and popular culture, from tapestries to ballads. By the time of Love’s Labour’s Lost, the Nine Worthies are well known enough to become comically misremembered by the middling-sort characters when they try and put on a masque for the aristocracy. It’s not chivalry being satirised there, but – much to the derision of the lords and ladies – the artistic pretentions of Holofernes, Nathaniel & co and their misappropriation of chivalric heritage, which is a slightly uncomfortable scene for a modern audience.

Even more excitingly, on the back of this I bought what I hope will turn out to be a magnificent historical bodice-ripper. The Vows of the Peacock, by Alice Walworth Graham (1955), is the story of Edward II, Isabella and Roger Mortimer. The blurb on the back tells me it’s about the ‘pageantry and scandal of a great court set aflame by a too-beautiful, too-ambitious woman’. Sounds just the ticket.