Well, that didn’t disappoint. I booked Les Liaisons Dangereuses in some trepidation, though: not only is it up there amongst my favourite novels, but for anyone of my generation, a revival will always evoke memories of the 1985 production with Lindsay Duncan and the late, lamented Alan Rickman, and the celebrated Stephen Frears film starring John Malkovich and Glenn Close.

Happily, Josie Rourke’s production at the Donmar Warehouse measures up.

The plot is gloriously serpentine: it centres on the Marquise de Merteuil (Janet McTeer) and the Vicomte de Valmont (Dominic West), former lovers whose favourite sport is sexual intrigue. Valmont wants to seduce the upright Madame de Tourvel (Elaine Cassidy); Merteuil wants him to corrupt Cécile de Volanges (Morfydd Clark), in order to take revenge on her former lover, who has left her to marry Cecéile, who is in love with the callow Chevalier Danceny (Edward Holcroft). Cécile succumbs to Valmont. Merteuil agrees that she will spend another night with Valmont, but only if he provides written proof of his seduction of Madame de Tourvel. And then the intrigues unravel when despite himself, Valmont falls in love with Tourvel and is forced by a furious Merteuil to break with her. It ends with Valmont killed in a duel with Danceny, the exposure of their letters to the public gaze, and the pervading sense of a doomed aristocratic class on the eve of the Revolution.

Janet McTeer, Dominic West as Merteuil and Valmont

Valmont and Merteuil exist in a series of masks, though their dissoluteness is tempered by self-knowledge and wit. But this is not just a play of surfaces; both are taken by surprise by their own emotions. Christopher Hampton’s superb adaptation, in which every line contains a dagger, more than does justice to Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ epistolary masterpiece, condensing four volumes into a couple of hours of theatre.

With such an eventful narrative there’s a danger it can tip into melodrama, so the casting is key. The leads have good chemistry. Dominic West’s Valmont is commanding and charismatic (though a couple of his lines are surprisingly shaky), while Janet McTeer is the right blend of deadly and charming, adept at playing the virtuous matron and counsellor who is trusted by Madame de Volanges (Adjoa Andoh) while at the same time helping to corrupt Cécile. Elaine Cassidy, in the difficult virtuous role as Madame de Tourvel, delicately articulates her inner struggle. The scene in which, confronted with her own desire for Valmont, she faints into his arms laces pathos with comedy and is particularly well done. There’s plenty of excellent work in the smaller parts, too: Jennifer Saayeng (last seen in City of Angels at the Donmar) as the courtesan Émilie, Una Stubbs as Madame de Rosemonde and Theo Barklem-Biggs as Valmont’s valet are all strong, though as Danceny Edward Holcroft is not so convincing.

Merteuil and Cécile

Sex as a weapon, deceit as strategy, seduction as social practice: Les Liaisons Dangereuses is all about the perils of pleasure. There’s pleasure for the viewer, too in the gorgeous costumes and the candles, and we merrily go along with the intrigue – with the exception of the uncomfortable scene of Valmont’s rape of Cécile. Valmont’s letters present it as a seduction, but the Donmar production allows us to see it through her eyes and therefore neatly wrongfoots the audience, since we’ve all been rooting for the sexy villains.

There’s one oddity about the Donmar production. The ending of Laclos’ novel sees Merteuil exposed; Valmont’s last act of revenge is to have their correspondence published. In Stephen Frears’ 1988 film, Glenn Close is booed at the opera and the last scene sees her savagely removing her face-paint, suggesting the disfigurement of smallpox she suffers in the novel. In the Howard Davies staging in 1985 the last scene was played out against a projection of a guillotine, suggesting how libertine aristocrats will soon be swept away (and perhaps uncomfortably suggesting the Terror as a moral broom). Here, though, the final scene, in which Cécile’s fate is decided by the three older women, hangs ambiguously. There’s a shadow in McTeer’s eyes at that point, as if she realises she’s tiring of the power games, but there’s no overt suggestion that Merteuil will be disgraced. It’s almost as if the whole cycle will begin again with a new set of lovers.

Madame de Tourvel

I’d forgotten how much Laclos’ main characters group novel-reading disparagingly with sentimentality. Hampton retains these references throughout his adaptation; when Madame de Tourvel is struggling with her love for Valmont, she reads Clarissa – the latter being the novel to which Laclos’ work is most strongly indebted. Laclos’ text also defines itself against the feminocentric novels of Madeleine de Scudéry, whose idealising romances were still being read in the eighteenth century in both France and England, but were increasingly being satirised within fiction. In Charlotte Lennox’s The Female Quixote (1752) the heroine Arabella makes a whole series of misjudgements because of her reading of French heroic romance, much as Catherine Morland does with the Gothic variety in Northanger Abbey. Female agency in Laclos is verbal and calculated, and the witty dialogue between Valmont and Merteuil rests on the assumption of intellectual equality. Pierre-Daniel Huet’s 1670 A Treatise of Romances (translated into English in 1672, Wing H3301) makes the connection between high narrative art and gender power relations, arguing that French romances are superior to any other nation’s because of

‘the refinement and politeness of our Galantry; which proceeds (in my opinion) from the great liberty in which the Men in France live with Women: these are in a manner recluses in Italy and Spain, and are separated from Men by so many obstacles, that they are scarce to be seen, and not to be spoken with at all’ ( p.103).

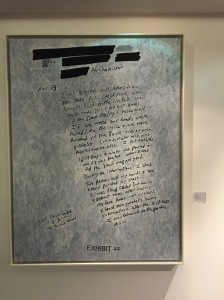

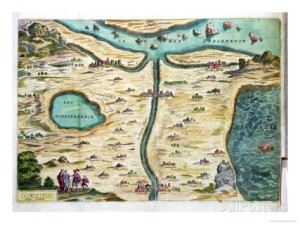

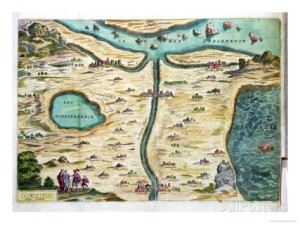

La Carte de Tendre

It’s a notion articulated strongly in Madeleine de Scudéry’s Clélie (1654), which introduced its readers to the Carte de Tendre, or the map of tenderness. Possibly a collective creation of Scudéry’s Paris salon, it’s a spatial representation of how heterosexual intimacy can and should progress. It begins at Nouvelle Amitié and presents three routes to ‘Tendre-sur-Reconnaissance’ ‘Tendre-sur-Inclination’ and ‘Tendre-sur-Estime’: gratitude, inclination and esteem. Along the way, the lover must pass through towns called Complaisance (obligingness), Petit Soins (small favours), or Obéissance (obedience), but there are dangers for the unwary traveller, who can wander to Negligence (neglect), Légereté (frivolity), Perfidie (treachery) and Orgeuil (pride) and potentially end up in the Mer d’Inimité (sea of Emnity). The most perilous endpoint, though is La Mer Dangereuse, a place of unbridled passion. The map still has the power to inspire now; Gucci’s head designer Alessandro Michele calls clothes ‘an atlas of the emotions’ and Gucci’s womenswear collection for spring this year included a print of La Carte de Tendre on a midi dress.

Gucci womenswear collection, Spring 2016

The Carte de Tendre regulates and authorises the emotional interactions between men and women, making them literally readable, though Boileau satirised this as a covert manual of seduction. Merteuil is with Boileau on this: she declares in the play:

‘I became a virtuoso of deceit. I consulted the strictest moralists to learn how to appear, philosophers to find out what to think, and novelists to see what I could get away with, and in the end, I distilled everything to one wonderfully simple principle: win or die.’

Merteuil’s philosophy of self-interest is diametrically opposed to Scudéry’s Carte de Tendre, but it gestures at a not dissimilar road map within relationships. What they both have in common is a horror of lack of control, or ‘la mer dangereuse’ of passion, and it is exactly that lack of control that forms Merteuil and Valmont’s downfall as they give in to love (or at least, a form of love). Les Liaisons Dangereuses not only figures the patterns of seduction as war, but also subverts the very notion of friendship – the highest possible relationship in Scudéry’s novel, which is presented as a form of perfect understanding. Valmont and Merteuil’s relationship is a twisted version of the friendship so valorised by Scudéry; there is only perfect understanding between Valmont and Merteuil when they share the same malicious objectives. Merteuil’s conviction that sex is the only power a woman can have is the cynical obverse of Clélie’s idealised view of negotiated relationships. Les Liaisons Dangereuses reverses the map of tenderness into a map of dazzling cruelty.